Oblatis Zero

Christian Andersen, Copenhagen

25.02 – 26.03.2011

Oblatis Zero, installation view.

Oblatis Zero, installation view.

Oblatis Zero, installation view.

Oblatis Zero, installation view.

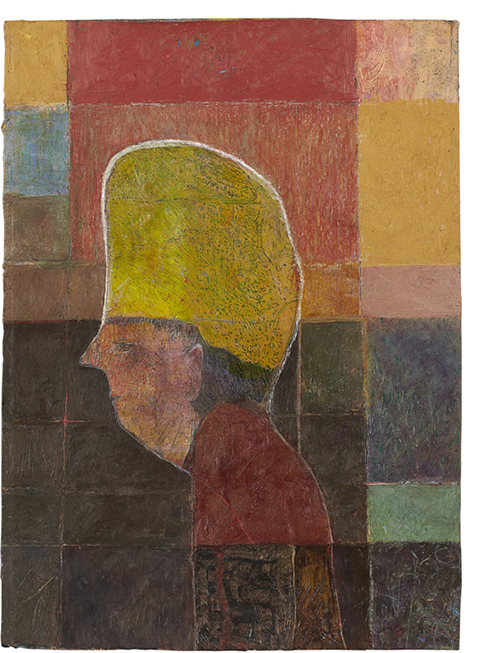

Untitled, 2011. Acrylic, crayon, paper, oil pastel on cardboard, 29,7 x 21 cm

Untitled, 2009. Acrylic, watercolour, crayon, oil pastel on paper, 29,7 x 21 cm

Untitled, 2011. Acrylic, crayon, oil pastel on found paper, 29,7 x 21 cm

Untitled, 2011. Acrylic, crayon, india ink, paper, oil pastel on paper, 33,5 x 23 cm

Have you never in your life, dear reader, come across people with the strange fancy of disliking

everything yellow, and yellow itself as a colour? One would think that a beautiful lemon, a

resplendent gold, a fiery orange, was something charming to look at. Where can the feeling of

aversion come in? And ask this same class of people what colour they do like, and they will all

answer as with one mouth: blue. Certainly, the azure of the celestial deeps is a sight to do one

good. But when evening frames the azure in gold, then surely the beautiful becomes something

more than beautiful and merges into the magnificent. Had I to choose between spending the

rest of my days in a maize-coloured or a sky-blue room, I should probably, of the two colours

named, prefer the yellow; but all the anti-yellowites to whom I have ever said so have always

laughed at me, and pitied my taste.

Well now, I invert the question; I ask you to tell me if you have ever met a man who said he

could not endure blue. Never, to a certainty. Never has anyone been found who abominated

blue. Whence comes it, now, that a certain class of mankind agree in their dislike of yellow,

and all agree in their liking for blue?

Colour-physics teach us that yellow and blue stand in a certain mutual relationship: they are

complementary colours, occupying as it were opposite poles. Is it possible that underneath

this fact something else lies hidden than the mere effect of the colour upon our eyesight?

Some more fundamental difference than the mere optical difference of colour familiar to all

of us, some difference which escapes our senses? And could there be appropriated to the

perception of such a difference a difference also of human faculty, a difference to the effect

that some might be able to perceive what is unrecognizable by others? Could there be, so to

speak, men with two sorts of senses? That would be a somewhat peculiar state of affairs.

Let us try and get further into it.

A girl, we may take it, is well enough pleased to see herself in the looking-glass. And perhaps,

also, there are men who take pleasure in the reflection of their own dear selves. And who could

begrudge them the pleasure, when a successful copy of God's lair masterpiece smiles back upon

them, and awakens anticipatory joy in the conquest which already flushes their cheek? Is there

anything in life more glorious or beatific than the beautiful Myself? How would it be though -

and it might really be possible - if there were girls, women, men, who shy of mirrors ? Who turn

away and cannot bear to see themselves in one? In very truth there are such persons. There are

men, and not a few in number, who are caused a peculiar feeling of distress by a looking-glass,

as though some sickly, repellent emanation came to them from it, so that they cannot stay quiet

there for a minute. It is not merely their own portrait that the mirror throws back to them; it

returns them also some indescribable, painful sort of impression, which some feel more and

others less, while to others it is only just so far perceptible as to leave them with a definite

dislike of mirrors. What is this? And what does it come from? Why do some men only

experience this feeling of repulsion? Why not all?

From Carl Reichenbach: "Die Sensitiven". In: Odisch-magnetische Briefe, 1852

Exhibition link